Products You May Like

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is a very old organisation in Indian polity and society and though it claims to be social in nature and intent, its influence on Indian politics is more than significant through its political arm, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). There have been studies, books and papers on the RSS and its worldview which largely centre around its origins to conclude that it is basically an upper Hindu caste, conservative organisation, which wants to establish Hindu Rashtra in India; is anti-Muslim, and is dangerous for the plural character of the country because it has a communal agenda. This particular narrative has existed since the national movement under Mahatma Gandhi, but post-independence has got shriller and bitter, with the Left starting to dominate Indian academia and educational syllabi. The result is that this particular narrative has over the years got ossified into the minds of an average liberal.

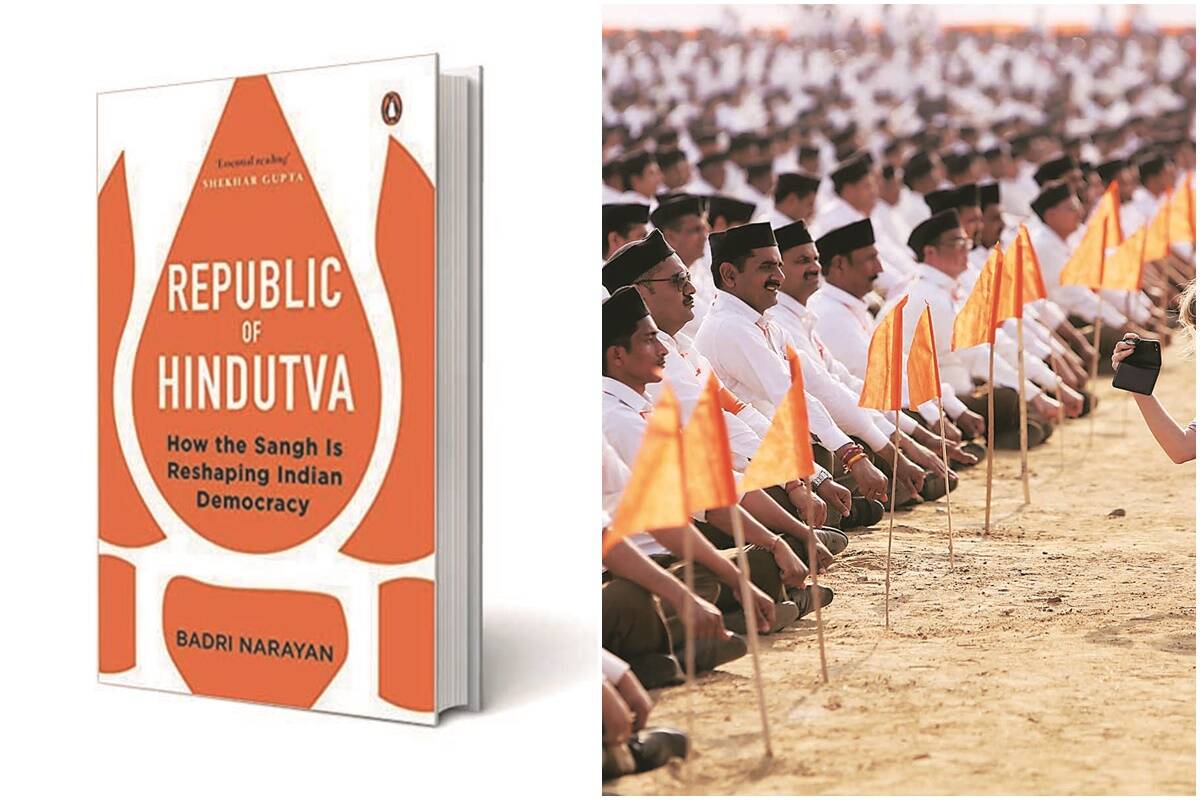

People are entitled to have their views on RSS and to propagate them, but the problem is that an ossified narrative only exacerbates a problem instead of countering it, for then the fight is ranged at a mirage rather than the real object. This in sum is the subject of social historian and cultural anthropologist Badri Narayan’s book, Republic of Hindutva: How the Sangh is Reshaping Indian Democracy. Narayan, who is director at the GB Pant Social Science Institute, Allahabad, is no polemic or post-modernist, but has based his work on extensive field research, especially in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. He holds no apologia for RSS or the Sangh Parivar, but equally true is that he has no great admiration for the ossified view of RSS that is mouthed by the so-called Left-Liberal intelligentsia of the country.

Related News

As he writes: “Political analysts who hold forth on the RSS in heated television debates do not understand the real power of the RSS. They use relatively superficial aspects like electoral successes and communalism to define the RSS. The problem of the Opposition is that they are fighting with an image of the RSS which is not its reality. The RSS is changing day by day but the politicians of the opposition parties are attacking the image of the RSS which is much older and has become obsolete. The political forces attacking the RSS are in fact attacking its shadow but are unable to understand the real RSS.”

If I may add from my side, the so-called Left-Liberal intelligentsia is so stuck in the 1930s Italy and Germany (Fascism and Nazism) that it has failed to notice that the world has changed. If the diagnosis is wrong, obviously the medicine prescribed will fail to work. Criticise, oppose, but at least keep yourself abreast of the changing realities on the ground. Here Narayan’s work can come in handy for the worst critics of the Sangh Parivar, but only if it is read with an open mind.

The electoral success of the BJP today, in which RSS has a big role to play, is a fact with which it has become difficult for its opponent to fight. What’s the reason behind this success? The lazy answer is, by playing the communal card and instilling a sense of insecurity in the minds of the majority religionists. But if that was so, wouldn’t have success come long back? Narayan lays bare how the RSS and its various outfits, both directly linked with it and several others which are loosely linked with it, have over the past few decades worked at grassroots to create a unified Hindu society by bringing the marginalised sections — Dalits, tribals, and backward castes — within its fold. It is this work, which involves building schools in the hinterlands, making temples for the icons of the Dalits, and giving prominence to their historical leaders, which has worked wonders for it. This has created a Hindu vote bank, which is almost unassailable if the contradictions are managed.

It is easy to test this hypothesis of Narayan in the laboratory of history. What was behind the success of Congress? It had the support of both upper and lower caste Hindus as well as Muslims. How did it lose this support base? By tilting towards one or few of the sections of its support base, meaning not being able to manage the contradictions of a coalition of class, caste, region, and religion. What was behind the rise of caste-based parties in various states, which challenged Congress’s hegemony? The main support base of these parties comprised the dominant castes with an alliance with Muslims. Since Muslims in most constituencies comprise 20-25% of the population, such alliances worked wonderfully. So in gist, there was no such thing as Hindu vote bank as it was fragmented. This kept back the BJP because its core support base was amongst urban, upper caste Hindus and trading classes.

So, what did the RSS do? It worked tirelessly to bring the Dalit, backwards and tribals into its fold. And how? By co-opting different and opposing ideologies in its fold. As Narayan says, “In the recent past, Dalit groups have identified with many minor characters in Hindu texts and presented them as symbols of injustice done to them. Efforts are being made to highlight such minor characters within the discourse of the Sangh, in which they and their identities could be given respect.” He has cited the case of Eklavya, a character in the Mahabharata who is described by the Sangh as a dharmaparayan Dalit (a dalit who follows his dharma).

Through field research in UP, Narayan highlights how RSS is fulfilling the religious aspirations of the Dalit and marginalised communities like Sahariya, Kabutara, Nat, and Sapera, among others. These communities want temples to be built for their local deities, which the Sangh fulfills. They want their local deities to be placed in temples alongside deities like Shiva, which RSS has been doing. These temples act as centres for marginalised communities to congregate, again fulfilling one of their deep seated desires.

Another strategy which has worked is changing the narrative of caste heroes of Dalits and backwards, which earlier used to be of discrimination at the hands of upper castes, into Hindu warriors and celebrating their anniversaries. One such is Suheldeo, whom the Pasi Rajbhar caste in UP considers their hero. The RSS launched a campaign to project Suheldeo as a Hindu hero because he allegedly defeated a Ghaznavid general.

Take this instance: At a political rally in Fatehpur during his election campaign in February 2017, PM Narendra Modi said, “If you create a Kabristaan (graveyard) in a village, then a Shamshaan (cremation ground) should be created.” The Left-Liberal intelligentsia labelled it communal, forgetting that it is the Dalits who work in Hindu cremation grounds, and by raising this issue, the BJP offered them a sense of inclusion.

Similarly, the Sangh co-opted backward castes by working amongst the non-Yadavs (OBCs) and non-Jatavs (SCs). The Yadavs form the main base of parties like Samajwadi Party in UP, and Rashtriya Janata Dal in Bihar. Similarly, the Jatavs are the main base of Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party. The Sangh/BJP has talked, worked, and to an extent succeeded in bringing about the concept of quota within quota. Since the jobs under reservation, etc, are mostly cornered by Yadavs and Jatavs as they form the creamy layer, this talk of quota within quota has worked well electorally for the BJP.

In short, the Sangh has understood well that whether it is Dalits, OBCs, or tribals they are not homogenous communities as is wrongly described in Leftist narrative. The heterogeneity amongst the marginalised sections has been tapped well by RSS/BJP.

The case studies done by Narayan and his team, which bring forth the ground realities that are so necessary to understand Indian politics and society, are no rocket science and could have been done by many other intellectuals and their think tanks. The reason the latter failed is because they work with a set of assumptions that are tailored to match their findings. Field research throws real outcomes if it is undertaken with an open mind, not with the ghost of Karl Marx dominating the analytical tools.

However, there’s one aspect where one feels Narayan could have dwelt more and in greater detail. How far is this strategy of co-opting the lower strata and weaving a unified Hindutva narrative sustainable, because on a micro level in rural areas hostilities amongst the upper and lower castes exist over several matters. Though Narayan has stated that fringe Hindu elements, not part of RSS and its affiliates, often spoil the party of the Sangh and pose a big challenge to the saffron outfit, perhaps he could have been more exhaustive here by citing some case studies.

Despite some such limitations, Narayan’s book is very insightful and is recommended reading for both critics as well as admirers of the RSS. For admirers to be mindful of the pitfalls, and for critics to at least know the enemy before mounting an attack.

Republic of Hindutva: How the Sangh is Reshaping Indian Democracy

Badri Narayan

Penguin Random House

Pp272, Rs 499

Get live Stock Prices from BSE, NSE, US Market and latest NAV, portfolio of Mutual Funds, Check out latest IPO News, Best Performing IPOs, calculate your tax by Income Tax Calculator, know market’s Top Gainers, Top Losers & Best Equity Funds. Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

Financial Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel and stay updated with the latest Biz news and updates.